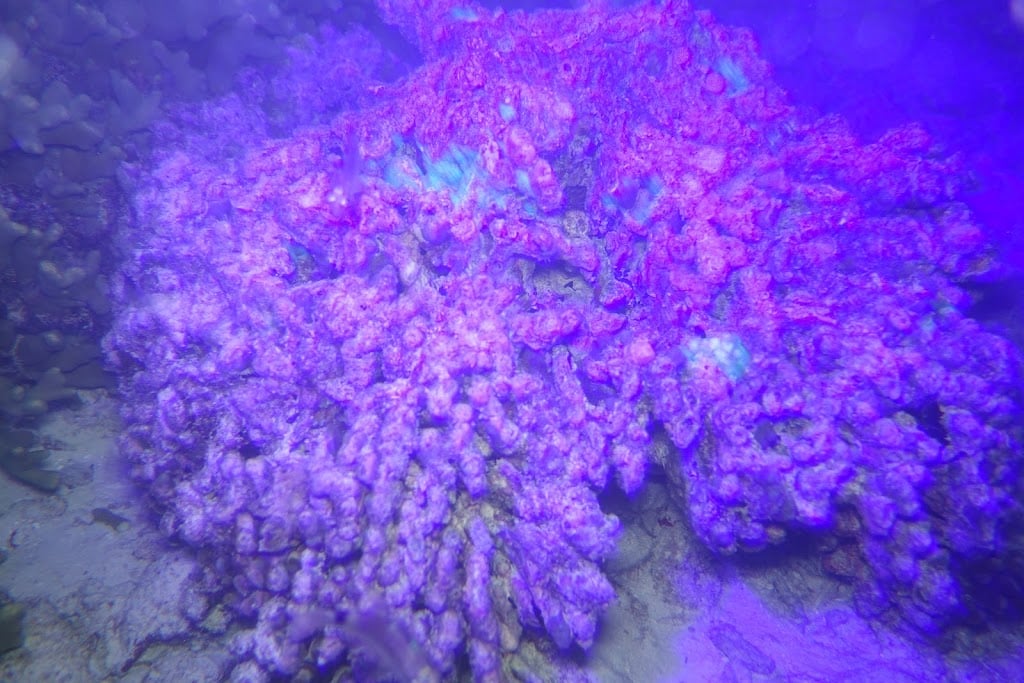

Are corals a shining beacon at night? Corals are not just a wonder to observe during the day, at night they glow. This isn’t just for our viewing benefit; it plays a vital role in the long term survival of coral.

|

| Fluorescence of Porites cylindrica |

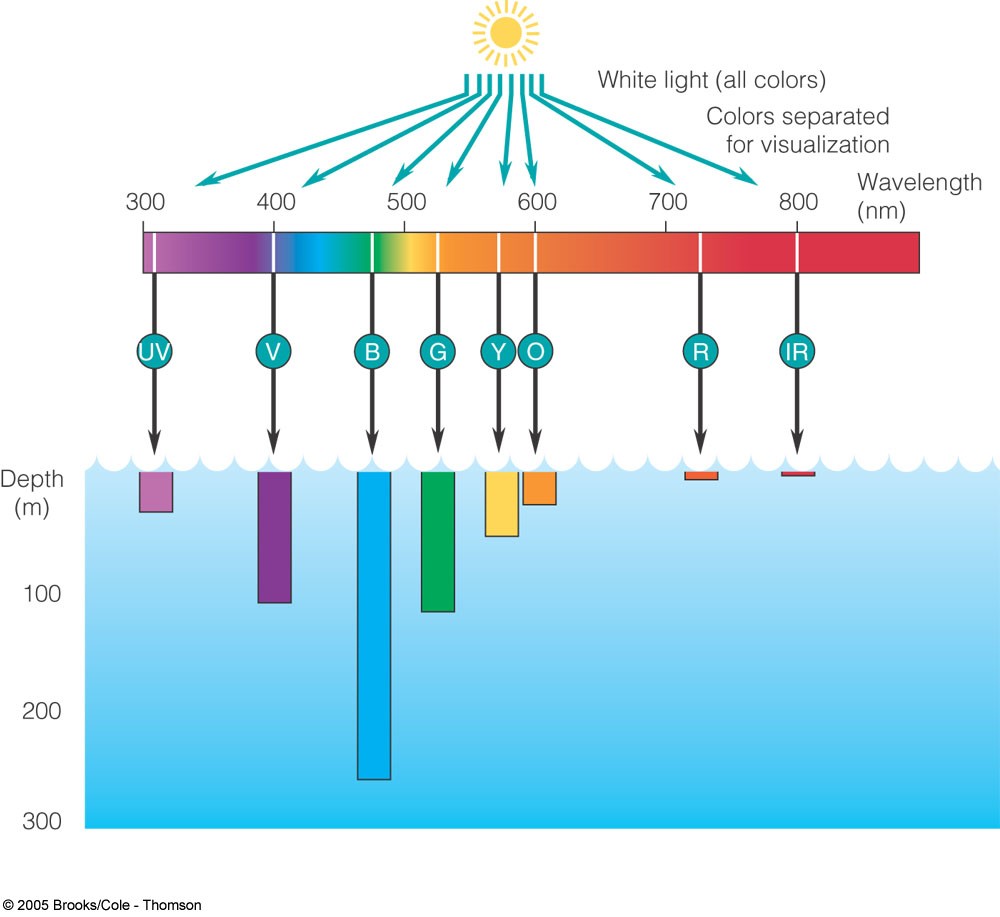

Due to the richness of life they create, corals are often described as the rainforests of the ocean. Their structural complexity supports one of the world’s most productive ecosystems providing ecological diversity and outstanding beauty. The coral animal (polyp) co-habitats its calcium carbonate skeleton with photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae harness energy from solar radiation and provide the polyp with 95% of its food. Coral is therefore limited to the habitat range of the algae, which in turn is limited by the penetration of the suns ray into the ocean; both the intensity and spectral diversity of light dramatically decreases with increasing depth. Although the blue/green portion of sunlight reaches depths of around 200m the algae requires the higher light levels found in the upper 30m of the ocean. Corals are therefore limited to the upper portion of the ocean; aptly named the sunlight ocean.

|

| Spectral diversity of white light (sunlight) and the depth that the light waves penetrate. Image credit to:http://ksuweb.kennesaw.edu |

The corals exposure to high light levels is crucial for its survival, but this is not without consequence. The high light intensity that corals are subjected to everyday can damage coral and zooxanthellae – similar to our skin and sunburn. Shallow water corals have a solution to this: fluorescence. The coral contains special pigments (green fluorescent pigments (GFP) and non-fluorescent chromoproteins (CP) which act as sunblock. The fluorescent pigments are in particularly high concentrations and contribute to the beautiful rainbows of colours which can be observed on the reef. When the coral is subjected to high sun exposure the pigment concentration increases, hence limiting the damage experienced by the algae when under stress from sunlight. The pigments are also involved in growth related activities, including repair. Injured coral will produce colourful patches concentrating these pigments around their injury site which prevents further cell damage. Some corals have been found to distribute fluorescent pigments around their tentacles and mouth to attract prey.

We are able to observe the fluorescent pigments when corals are illuminated at specific wavelengths (generally blue light). In high pigment concentrations corals can become shining beacons at night. Light is absorbed by the pigments and then re-emitted. During this process some energy is lost resulting in a different colour being observed – generally green. During our blue light night snorkel it is possible to see corals glowing on the house reef at Gili Lankanfushi.

|

| Fluorescence of Porites cylindrica |

It is now widely accepted that fluorescent pigments aid in sun protection, so why do corals below 30m still have these pigments? In shallow reefs generally only green fluorescence is observed, whereas in the mesophotic zone (between 30 – 100m) corals shine green, orange, yellow and red. Fluorescent pigments are energetically costly to create, therefore the pigments must have a biological purpose, or else they would not exist at this depth. A study carried out by the University of Southampton found that deeper corals produce fluorescence without light exposure, which suggests that these corals are not producing pigments for sun protection. It is suspected that the corals are producing pigments to transform short light wavelengths received into longer wavelengths to enhance algae photosynthesis, thus producing more food for the polyp. It has also been suggested that it may link to behaviour of reef fish, although more studies are required. Next time you are night diving take a look. Harnessing these fluorescent pigments could pose significant advances for medical, commercial and ecological purposes.

|

| Many Acropora species also have fluorescent pigments. Credits to: Reef Works |

Marine biologists at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at San Diego have suggested that monitoring fluorescence could be an easy and less invasive way to monitor reef health. Scientists measured the fluorescence levels after corals were exposed to cold and heat stress. The levels were reduced when exposed to both stresses, although coral subjected to cold stress adapted and fluorescence levels returned to normal. Corals subjected to heat stress lost their algae and starved. Therefore, if high fluorescence levels are observed it suggests that the reef has a healthy coral population. Additionally there are many medical benefits that can be gained through the understanding and utilisation of coral fluorescence.

There are promising applications for biomedical imaging, for example pigments can be used to tag certain cells e.g. cancer cells which can then be easily viewed under the microscope. The fluorescent pigments also have the potential to be used in sun screen. Fish feeding on coral benefit from the fluorescent pigments which suggests that the pigments move up the tropic levels (food chain). Senior lecturer from King’s College London and project leader of coral sunscreen research, Paul Long and his team have suggested that if the transportation pathway up the food chain is identified it may be possible to use this to protect our skin against UV rays in the form of a tablet. This could a break-through in terms of reef safe sun screen.

There are promising applications for biomedical imaging, for example pigments can be used to tag certain cells e.g. cancer cells which can then be easily viewed under the microscope. The fluorescent pigments also have the potential to be used in sun screen. Fish feeding on coral benefit from the fluorescent pigments which suggests that the pigments move up the tropic levels (food chain). Senior lecturer from King’s College London and project leader of coral sunscreen research, Paul Long and his team have suggested that if the transportation pathway up the food chain is identified it may be possible to use this to protect our skin against UV rays in the form of a tablet. This could a break-through in terms of reef safe sun screen.

Next time you are night snorkeling shine a blue light on the corals and view this natural wonder yourself!